Categories: Sightseeing / Travel

Bathhouse Row in Hot Springs, Arkansas

The 2nd day of my 4th date with Jeff was a blast! Unlike the previous day, our agenda was seeing the 8 bathhouses up close and personal. Each bathhouse has its own architectural design and is the 3rd or 4th generation (the first generations were destroyed by fire having been built with wood). They’re all relatively the same height. I’m just glad the weather cooperated while we clicked away, going from one bathhouse to the next. A few times we dashed for cover when drizzling commenced, and Mother Nature was kind enough to give us some reprieves. I don’t how the paparazzi do this for a living because I’d suck staking out in the rain and cold weather.

Excerpts from a brochure (distributed by the National Park Service):

Old documents show that American Indians knew about and bathed in the hot springs during the late 1700s and early 1800s. Some believe that the traces of minerals and an average temperature of 143 degrees F (62 degrees C) give the waters whatever therapeutic properties they may have. People also drink the waters from the cold springs, which have different chemical components and properties. Besides determining the chemical composition and origins of the waters, scientists have determined that the waters emerging from these hot springs are over 4,000 years old. The park collects 700,000 gallons a day for use in the public drinking fountains and bathhouses. The water is tested regularly to ensure quality. Today green boxes cover most of the 47 springs to prevent contamination.

French trappers, hunters, and traders became familiar with this region during the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1803 the United States acquired the area when it purchased the Louisiana Territory from France. The next year President Thomas Jefferson dispatched an expedition led by William Dunbar and George Hunter to explore the newly acquired springs. In 1832 the federal government took the unprecedented step of setting aside four sections of land. It was the first U.S. reservation created to protect a natural resource.

Hot Springs National Park is not in a volcanic region. The water is heated by a different process. Pores and fractures in the rock conduct the water deep into the Earth. As the water percolates downward, increasingly warmer rock heats it at a rate of about of 4 degrees F every 300 feet. In the process the water dissolves minerals out of the rock. Eventually the water meets faults and joints leading up to the lower west slope of Hot Springs Mountain, where it surfaces.

The first bathhouses were crude canvas and lumber structures, little more than tents perched over individual springs or reservoirs carved out of the rock. Later, businessmen built wooden structures, but they frequently burned, collapsed because of shoddy construction, or rotted due to continued exposure to water and steam. Hot Springs Creek, which ran right through the middle of all this activity, drained its own watershed and collected the runoff of the springs. In 1884 the federal government put the creek into a channel, roofed it over, and laid a road above it. Much of it runs beneath Central Avenue today.

We parked near the Arlington Hotel and worked our way down (southward).

Hot Springs’ nickname is “Valley of Vapors”

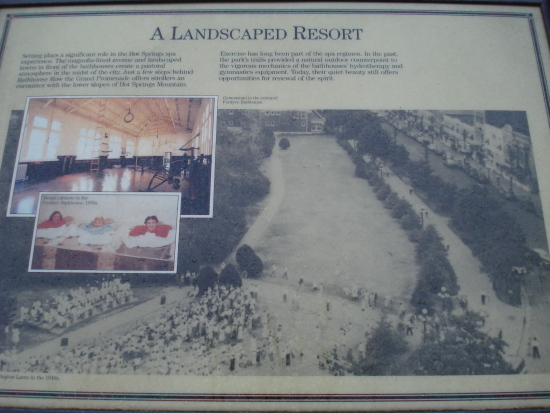

“Setting plays a significant role in the Hot Springs spa experience. The magnolia-lined avenue and landscaped lawns in front of the bathhouses create a pastoral atmosphere in the midst of the city. Just a few steps behind Bathhouse Row, the Grand Promenade offers strollers an encounter with the lower slopes of Hot Springs Mountain.

Exercise has long been part of the spa regimen. In the past, the park’s trails provided a natural outdoor counterpoint to the vigorous mechanics of the bathhouses’ hydrotherapy and gymnastics equipment. Today, their quiet beauty still offers opportunities for renewal of the spirit.”

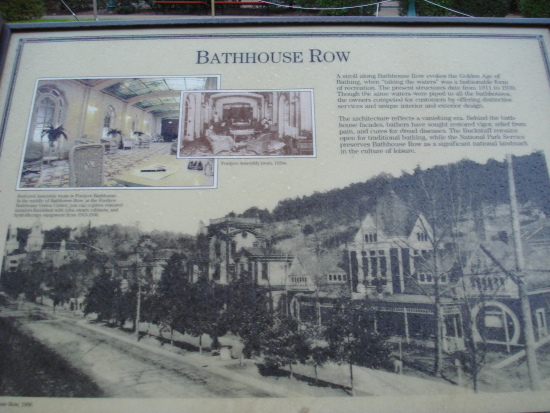

“A stroll along Bathhouse Row evokes the Golden Age of Bathing, when “taking the waters” was a fashionable form of recreation. The present structures date from 1911 to 1939. Though the same waters were piped to all the bathhouses, the owners competed for customers by offering distinctive services and uniqute interior and exterior design.

The architecture reflects a vanishing era. Behind the bathhouse facades, bathers have sought restored vigor, relief from pain, and cures for dread diseases. The Buckstaff remains open for traditional bathing, while the National Park Service preserves Bathhouse Row as a significant national landmark in the culture of leisure.”

Superior Bathhouse

Built in 1916; closed 1983

Superior Bathhouse

Classical Revival architectural style

Hale Bathhouse

Renovated in 1919 and again in late 1930s; closed 1978

Hale Bathhouse

Spanish Revival (Mission Style)

Maurice Bathhouse

Built in 1912, closed 1974

Maurice Bathhouse

Combination of Renaissance Revival and Mediterranean styles

The Stevens Balustrade (in between the Maurice & Fordyce Bathhouses towards the back)

The inscription above the drinking fountain states “1892, Captain Robert R. Stevens USA Engineer, 1895”

Natural spring behind one of the bathhouses

Fountain just outside the Fordyce Bathhouse

Above the inscription “U.S. Hot Springs Reservation” are the dates “1889-1893”

Wherever you saw water outdoors, you can count on seeing steam too

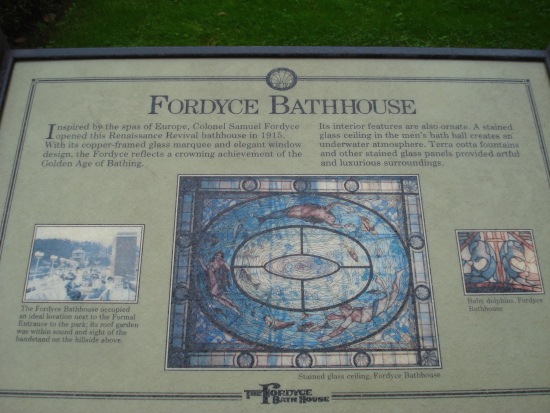

Fordyce Bathhouse (built in 1915, closed 1962)

Open as a Visitor Center where the tubs, steam cabinets, showers, and hydrotherapy equipment from 1915-1936 can be viewed

Fordyce Bathhouse

Renaissance Revival style

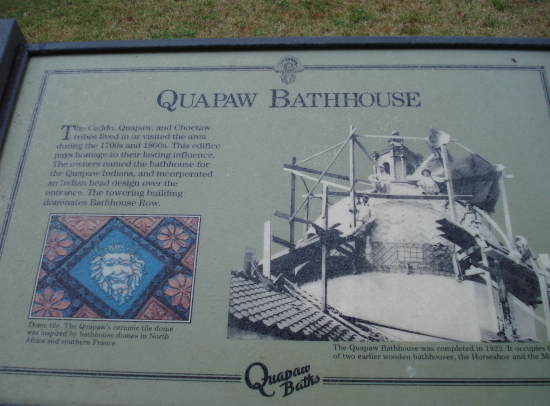

Quapaw Bathhouse

Built in 1922, closed 1984……..reopened under the name “Quapaw Baths and Spa” in Summer 2008

Quapaw Bathhouse

Spanish Colonial Revival style

To view photo in Flickr, go to http://www.flickr.com/photos/yummies4tummies/4270456623

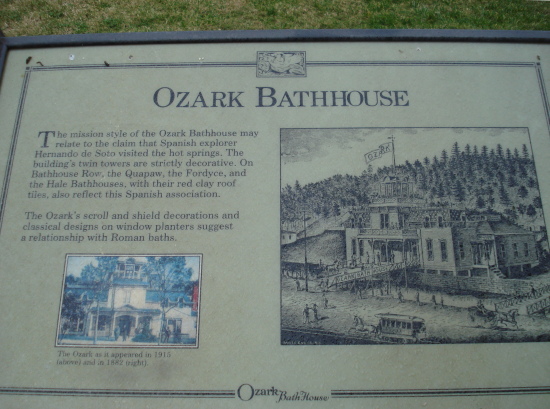

Ozark Bathhouse

Built in 1922, closed 1977

Ozark Bathhouse

Spanish Colonial Revival style

Buckstaff Bathhouse

Operational since 1912

Neoclassical Revival style

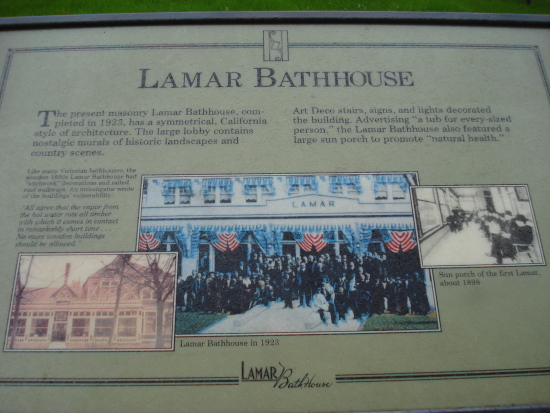

Lamar Bathhouse

Built in 1923, closed 1985

Transitional style

Stay tuned for our tour of the Fordyce Bathhouse (Visitor Center)…

Tags:

Tags:

Discussion

No comments for “Bathhouse Row in Hot Springs, Arkansas”

Post a comment